Electrified Echoes at Callirrhoë, Athens

“Electrified Echoes“ explores themes of transformation, loss, and renewal, reflecting the intersections of Stamkopoulos’ artistic journey with his experiences in Berlin’s dynamic cultural and musical landscape. Yorgos Stamkopoulos has spent most of his adult life in Berlin, where he developed his career as a painter. Alongside his painting practice, Stamkopoulos created visuals for DJs performing at the iconic Watergate club, a cornerstone of Berlin’s clubbing history. This parallel activity not only influenced his creative process but also provided a space of freedom, solidarity, and unrestrained creativity that left a profound mark on his work.

The Watergate club, founded during Berlin’s post-Wall era, embodied the ethics of non-hierarchical power, antiracism, anti-war movements, and acommitment to queer, feminist, and anticonformist ideals. Recently, the club closed its doors for good, marking the end of an era—not only for Berlin’s cultural scene but also for Stamkopoulos, whose life and work were deeply intertwined with this space.

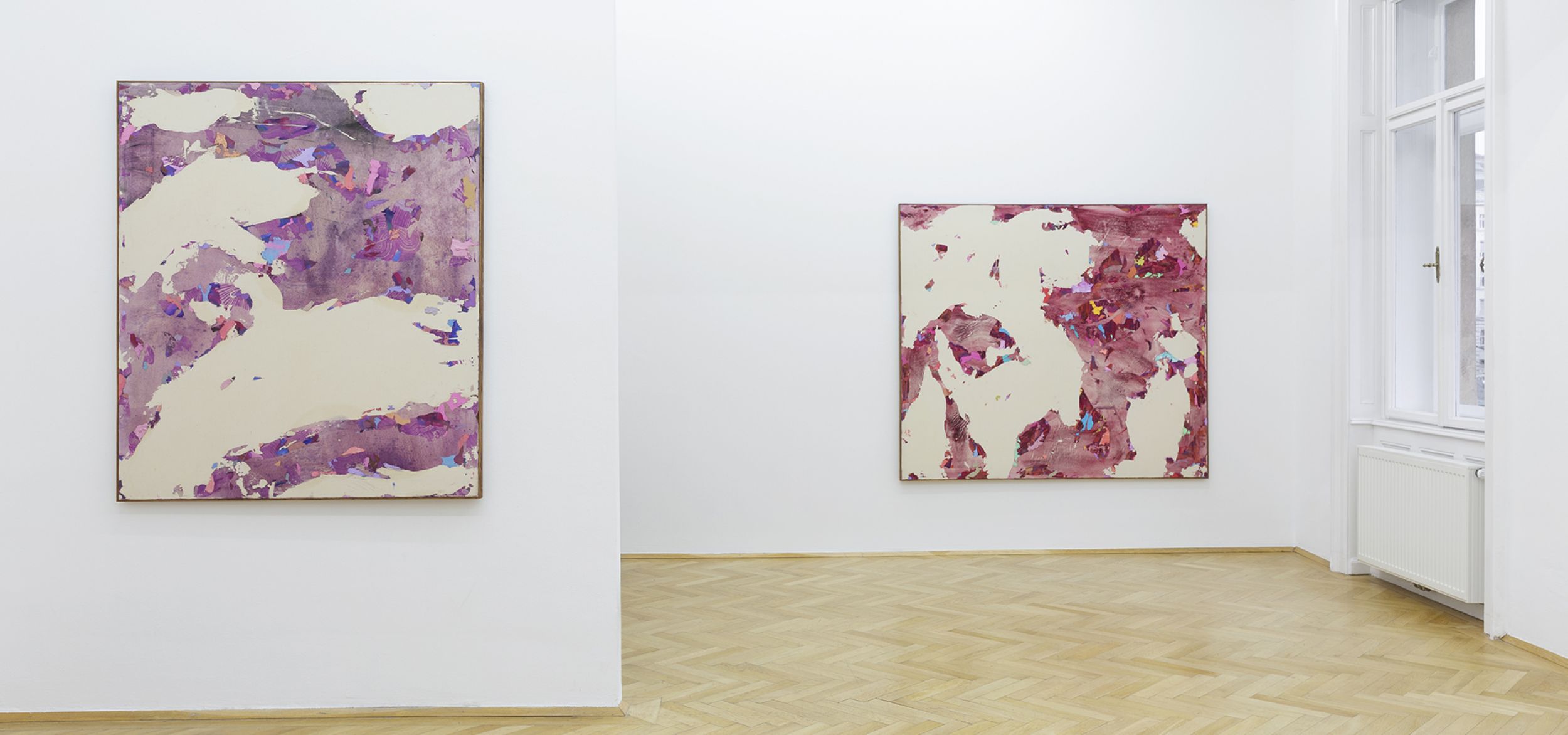

The new body of work presented in “Electrified Echoes“ is imbued with a sense of this loss, which simultaneously functions as a point of departure. With boldness, density, and empowerment, Stamkopoulos’ paintings capture the vitality of music, the ritualistic intensity of the club experience, and the universal role of such spaces as safe havens fostering community, creativity, and alternative forms of connection.

The exhibition also offers a rare opportunity to trace the evolution of the artist’s creative process over the past twenty years. Drawing inspiration from the abstract and nuanced colors found in both music and nature, Stamkopoulos creates artworks that eloquently capture the transformative beauty inherent in the world around us. His technique begins with the application of a masking agent to the canvas, followed by gestural painting. After allowing this initial layer to dry, he alternates between applying a masking agent and oil paints, creating a multilayered process with unpredictable shapes and areas left without paint. Once the entire canvas is covered, he scrapes off the paint, adding depth and complexity to his dynamic and textured works. This method mirrors the transformative process of molding, resulting in canvases that are both visually and texturally rich.

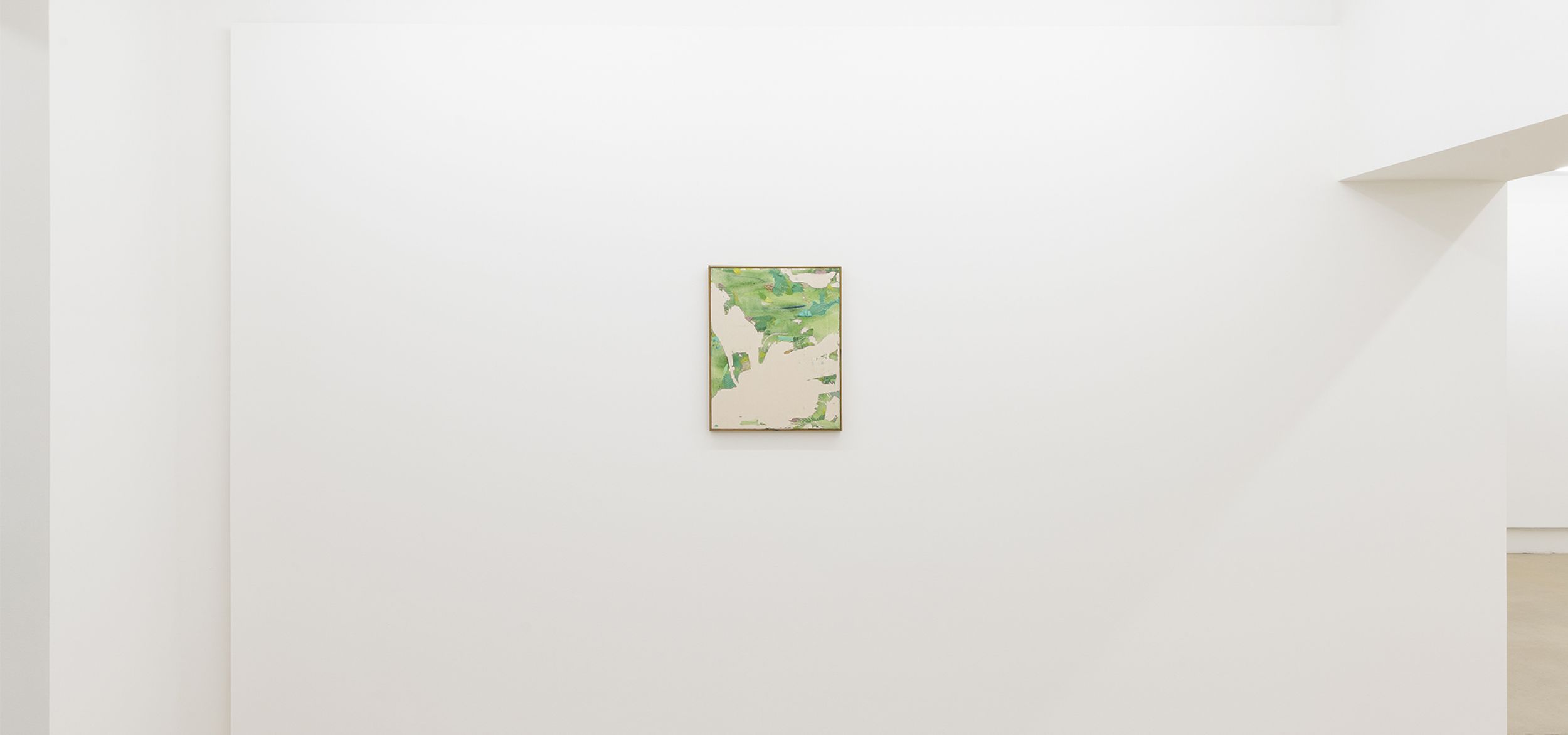

In contrast to his earlier works, where the depiction of empty space is prominent, allowing the artist to create imaginative landscapes, in his new work, it seems as though he is distancing himself from the empty space. This rejection of empty space appears both as a need for detachment from the established and as a result of an internal drive to activate a larger pictorial field, where color and movement play a central role in the final outcome of the piece. The boundaries and forms are no longer as distinct, referring instead to continuous motion. According to the artist, the works in this series no longer possess the stillness of the previous ones.

“Electrified Echoes“ offers a poignant reflection on the intersection of personal and collective histories, capturing both the fleeting nature of cultural moments and the enduring power of art. Through this exhibition, Stamkopoulos invites viewers to experience the pulse of Berlin’s vibrant scene while contemplating the larger forces of change, loss, and rebirth. It is a celebration of artistic resilience, where memory and imagination converge to forge new paths forward.

Oscillations at Collectors Agenda, Vienna

The works by Greek artist Yorgos Stamkopoulos defy conventional boundaries of the process of painting by challenging the norm where control over the artwork is often deemed crucial. His work becomes a play between control and unpredictability, structure, and chaos. By layering and removing paint on the canvas, the artist achieves a dynamic surface that bears both the traces of his hand and those of chance. His works are not just visual representations but multifaceted explorations of the artistic process itself that are not limited to the medium of painting but extend to ceramics and bronze sculptures. The dazzling compositions feature abstract forms, expanses of colour, and seemingly endless lines. Within his process, the artist applies a casting material, forming a skin-like layer over the canvas. Subsequent tiers of paint are added by the artist, only to be later removed, yielding his sublime paintings.

Besides paintings, Yorgos Stamkopoulos presents a new series of untitled ceramic works. The series is crafted from a negative print of one of the artist’s earlier works—a sort of artistic footprint. Once the painting was made, it was intentionally destroyed, yet its essence remains captured. Stamkopoulos employs this technique to retain the memory, aura, and impact of the original piece, all without the need for its physical presence. The fired clay, subsequently glazed, lends the work a charming naivety and playful allure. Unlike painting on canvas, where control over the medium is more evident, here Stamkopoulos had to exercise restraint in the process. Ultimately, this series serves as a poignant reflection on the intricate interplay of memory and time.

The works of both Ilari Hautamäki and Yorgos Stamkopoulos intersect through their intuitive, impulsive and organic artistic expressions, bridging the divide between abstract formal language and a mutual exploration of the essence of memory.

In juxtaposition, Ilari Hautamäki’s rather abstract, rhythmic, and gestural works form interesting connections with Yorgos Stamkopoulos unpredictable, romantic painterly language. Classic paintings meet fired, glazed clay and the aura of Finnish nature encounters the shimmering lights that can be found in the Greek countryside. A different type of landscape evolves, dense with motion that emanates from the techniques of both artists.

This exhibition acts as a cartography of the mind, probing the potential of artworks as mnemonic devices and tools to aid memory. It’s akin to strolling through the gardens or the personal archives of the two artists, where only imprints of documents remain, revealing traces of information in the form of fragmented images reminiscent of relics.

Touch Me, Don’t Touch Me at ZellerVanAlmsick ,Vienna

In utero touch is the first sense that we develop as humans. From a young age we’re told “don’t touch the stove” and what do we do if we wake up in the middle of the night? Grasp around in the dark. Throughout our lives, touch is a moment of physical connection that gives us a greater understanding of the world around us. What does it then mean when these enticing moments of touch lead to additional confusion instead, and the act of touching is warped from a process of learning to one of unlearning? It is precisely this subversion of expectations that both Yorgos Stamkopoulos and Bianca Phos play with in the materiality and conceptualisation of their work.

Since Giorgio Vasari introduced the idea of disegno during the Renaissance, the idea that the artist can transpose his abstract genius by the touch of his pencil or paintbrush to canvas has been a core principle of Art History. However, in the process of making his works, Yorgos Stamkopoulos turns this idea on its head. Unlike the Renaissance genius who can control his creation by the careful placement of his brush, Stamkopoulos can never fully determine the outcome of his efforts. Methodically applying layer upon layer of paint, he undermines his own agency by peeling away the top layer of paint once the canvas is completely saturated. It is a way of working Stamkopoulos likens to the process of casting a sculpture rather than painting; at the end of the day, the final work can never be fully controlled by himself alone.

Like peeling away a second skin, Stamkopoulos intentionally lays his artistic practice bear. Exposing the indeterminate messy underlayer is of greater interest to him than presenting a final perfected piece. It is no longer just the visual but also the visceral aspects of his work that are now equally important. With no recognisable figures or objects depicted the viewer is left to make up their own associations. However, in addition to the usual questions posed by abstract painting, the mystery shrouding Stamkopoulos’ process further avoids an easy answer or explanation. All the viewer is left with is their subjective encounter with the work, how it individually touched them.

Bianca Phos on the other hand, considers touch more abstractly as one of the many stimuli that affect how we embody our environments. Her sculptures are formally inspired by illustrations of neural pathways in animals and humans, but Phos chooses to materialise these internal structures with a playful materiality. At first glance, the works teeter on the edge of violence; sharp steel discs come dangerously close to cutting soft leathery tendrils. However, upon closer inspection, these disks bear the scars of weathering caused by rain or exposure to fire, whereas the seemingly soft leather has been shrunken and hardened by exposure to boiling water. Touched by external forces, all materials have inherently changed.

Yet this is not a process Phos can fully control either, which is why her sculptures perfectly embody how we internalise the world around us. Our bodies are persistently exposed to stimuli, but the significance of these forces vary from person-to-person and are in constant flux. The touch of a friend one day, can become that of a lover the next. Likewise, how this information is processed and once more externalised by the individual is unpredictable. In this way, Phos considers bodies as porous membranes into which information constantly flows, is translated, and then regurgitated. Every action has an indeterminable reaction leaving us not only vulnerable to the outside world, but the outside world also vulnerable to our response. The result is an infinite number of unpredictable entanglements between us and not only other living organisms, but also our surrounding environment.

And yet, rather than shying away from this unpredictability, Yorgos Stamkopoulos and Bianca Phos both place it at the centre of their practices. Touch me, don’t touch me; understanding is both important and not important when encountering their work. As artists, it is impossible for them to fully predict how others will respond to their creations. It can lead to deeper associations – a way of understanding art or even oneself – but at the end of the day, both artists invite you to relish in the questions themselves rather than any clear answers.

Hannah Marynissen

As Time Goes By at einsgallery, Limassol

What about time, picture and abstraction? The picture does not only represent a visual offering to the viewer. A picture is a material product that registers a sequence of conscious decisions which took place in a concrete time frame and enters into a space of the aesthetic present. Abstraction or more precisely abstract paintings illustrate a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can interpretate.

Examining the work of Yorgos Stamkopoulos becomes clear that the subject matter of his paintings has to do with the process and the becoming. Since the act of painting in itself is the most typical or inherent process, the process of painting becomes the most integral and natural metaphor that painting itself can use. The color impregnates the space. The lines and the gestures themselves are acting as the agent of illusionism.

While his earlier works conveyed a feeling of floating objects as part of a bigger whole through airbrushed strokes and isolated symbols on the canvas surface, the recent paintings of Yorgos Stamkopoulos embrace a different type of landscape. Dense with motion – that occurs from the technique used by the artist – the artworks swarm with gestures that range from wispy to bold. They wrest from elements that are being added and then removed a sense of coincident. The artworks depart from utilizing vivid coloration, have a more restricted palette, diversified between red and blue and they could be efficiently characterized as a way of reinventing landscape. They evoke in a way the natural environment. His abstract pictures glow with the same shimmering light that can be found in the Greek countryside. The swerves and switchbacks of his stacked bands can be quickly observed as parallel lines of waves approaching a beach, swelling and breaking as they near the shore or as the wind that passes by a plateau. The emotional expression of the artist is throughout discernible.

Robert Roseblum coined the term abstract sublime to describe the way that the paintings can call to mind a sense of the immensity and power of nature comparable to that found in the landscapes of painters of former artistic movementes such as Romanticism. As Pepe Karmel wrote: „While the sublime may be out of fashion, references to the natural landscape persist in contemporary abstraction.“.

Olympia Tzortzi

Another Perfect Day at Nir Altman, Munich

In almost all of the texts on Yorgos Stamkopoulos‘ painting, and in nearly all of the conversations I have had about it, the talk has always quickly turned to the creation process of his painting; directly drawing on lines connecting to art historical currents, and quickly falling on the word décollage. This is undoubtedly an extremely exciting aspect of his work, as he uses a casting material to lay a kind of skin on the canvas, then covering it with layers of paint, and finally removing the dermis to create ramified structures of color fields and voids.

Nevertheless, in this fixation on the process, I would like to point out that the paintings have changed considerably over the last five years, while the process has remained the same. Of course, the works are still defined by the linen-colored imperfections and the colors washed out by the masking agent; and yet these two moments seem to be organized quite differently in the newer works. The rhythm of both poles, of painted surfaces and missing parts, seems strongly altered. Even if it is an inadmissible step, we can assume a coastal formation, photographed from the air or space, as a crest of understanding. But this comparison does not only make sense because of the shapes. Since we are dealing with large canvases, the question of the distance that lies within them is beneficial. On the washed out blue and green of the color fields, which exist in the distance above all as form, there are stranded color breaks; thick pasty chunks, like a sum of small counterpoints distributed over the ground. Stamkopoulos deliberately thwarted harmonies here and placed small screeching bastard-hybrids in the color families. These little disturbances break up the distanced perspective and draw you into the picture.

And indeed, the new works—not only because of their large format—have an immersive quality, a pull that is comparable to falling into a landscape from a great height. When I think about it, he and I mostly spoke about those artists who could provoke such a devouring effect by means of their color use or painting style. James Turrell perhaps, Jules Olitski, Christine Streuli. But also Morris Louis, whose reaction-mixed color combinations of Unfurled Paintings and Stripe Paintings may have served as a model for Stamkopoulos’ use of color in Another Perfect Day. Louis also seems to be an important point of reference because he has succeeded in suggestively charging the emptiness of the medium—and the void is central to Stamkopoulos’ paintings; which is emphasized by the critical view of just that technique, by which these gaps occur. More importantly, the art historical position of Morris Louis. After all, it was the perfect illustration of Greenberg’s flattening of painting, and thus almost its endpoint, since the innovative potential of this form of painting had been exhausted. In the meantime, the majority of painting has turned back to what Greenberg mocked as ‘literary content’ through a few neo-expressionist spasms. It is all the more significant when a painter goes back to this supposed dead end (this is how I understand the trace, which Stamkopoulos attributes here to Louis) and looks for ways to revitalize this tradition under new auspices and a different temporal context. Maybe there’s some embers left under the ashes.

Moritz Scheper

Worlds Beneath at Nathalie Halgand, Vienna

Yorgos Stamkopoulos’s paintings are more than paintings. They are shadow sculptures—the remains of what was. Each work is the final trace of a thick ‘skin’ built up with casting material on canvas, over which layers of colour and paint are applied before the final dermis is peeled off, and the subtle imprint beneath is revealed. The fleshy clumps that we don’t see are visceral, messy, and tangible; they have absorbed the intensity of an abstract and expressive approach that is instinctive, physical, and spontaneous. The intimacy of each painting’s making might explain why their membranes are not shown alongside Stamkopoulos’s finished canvases—they are the residues of a personal and corporal encounter between one artist and the void; the record of a private conversation.

When these skins are peeled off, the canvases transform; as does the artist’s relationship with their surfaces. From an act of unencumbered application, the artist now begins a considered subtraction, in which his compositions are delicately undone—there is no telling how the casting material might behave when it is pulled off, or what will remain once the process is complete. A balancing act is caught in each work: an equilibrium that feels at once intensely deliberated and measurably unhinged. Intersections of colour, stroke, and line are tempered by carefully revealed swathes of raw canvas that glow like luminous intervals,[i] with the additive and subtractive levelled as equal partners on the image plane. Here, a multitude of dynamics—between depth and surface, time and space, subject and object—commingle and interact in what could only be described as a dance. Such elegant dialectics bring to mind Vilém Flusser’s description of technical images. Even if Stamkopoulos’s pictures are not made using technoglogical devices, the observer is still confronted with “mosaics assembled from particles” rather than surfaces; fields of matter “emerging into a post-historical, dimensionless state.”[ii]

It is fitting that Stamkopoulos refers to the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset’s 1925 essay, “The Dehumanization of Art,” when discussing his work. Ortega identifies a “new style” of art that aspires to “scrupulous realization,” in which artists do not take ideas to be “synonymous with reality,” but consider them “for what they are”—“mere subjective patterns” to make live, lean, angular, pure and transparent.[iii] To borrow Peter Halley’s reading of Ortega, “the Modernist artist reverses the ‘spontaneous’ movement from world to mind [iv]—an engagement with the unruly universe of ideas that recalls what Stamkopoulos captures in a frame, in which—to paraphrase Ortega—the subjective is objectified and the imminent is worldified.[v] Each canvas is an object testimony of a subjective journey into that known and unknown space of pure and ineffable possibility, which art has so often sought out. They are portals to this potent abyss: both a way in, and a way out.

Stephanie Bailey

[i] This phrase comes from Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1923 book, The Saviours of God: Spiritual Exercises.

[ii] Vilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images (University of Minnesota Press: 2013), p. 6.

[iii] As quoted by Halley in “Against Postmodernism,” p. 58.

[iv] Peter Halley, “Against Postmodernism,” Selected Essays, 1981–2000 (Edgewise Press: 2013), p. 58.[v] As quoted by Halley in “Against Postmodernism,” p. 58.

A Timeless Tale at Kunst&Denker, Düsseldorf

As the title of the exhibition reveals, the process-based works of Yorgos Stamkopoulos are a boundless painting action around a timeless story. Lines that have no beginning and no end; abstract forms created by addition and subtraction, as in a sculptural process; works, which are held in pleasant colors and play in different proportions with our perception.

By applying a layer of insulating material before using paint, which prevents contact with the canvas, a picture is created layer by layer, which only partially finds its way onto the canvas. On the previous works Stamkopoulos sprayed colors, which kept him on a distance from the painting surface. In his current works he turns back on using oil painting with brushes, which allows him to savor the full range of pastos. In the end, the layers can – like a mask- be removed as a whole and it only those parts of the painted canvas are visible on which there was no insulating material. The works represent nothing, except the own creative history, and thus refer to the dominant moment of gestures in painting.

The viewer is confronted with a multi-layered painting and a strong play of materials-materials that are visible on the canvas, but also those that Stamkopoulos removed during his painting process and are no longer visible. The artistic result expresses the gestural subconscious of the artist. The seemingly unpainted parts of the canvas claim the need for free space within the strict framework of painting to allow a freedom of association and critical thinking. Covering and Unveiling, Expectation and Randomness, Impulse and Correction – opposing pairs meeting in the work of Yorgos Stamkopoulos.

Trajectory at Mario Iannelli, Rome

‘Trajectory’ is the title of the solo exhibition that Yorgos Stamkopoulos has created especially for Galleria Mario Iannelli in Rome. The exhibition is a unique location-based work which is born from the distinctive coexistence of the painter’s work on the walls of the architectural space – fragments of monochrome colours, combining freely to create a composition that brings the environment to life and/or renders it uniform – and a series of sculptures that scan the space and characterise discovery.

The particular means of dialogue that the artist establishes between the wall painting and the three-dimensional presences – steel lines that soar upwards from the ground like the result of an independent but alienating power – change not only the viewer’s perception of the space, but also their way of inhabiting and measuring the physical context in which they find themselves. As the artist himself explains: “The idea of wall painting had been floating around in my head for quite some time! The sculptures are made from steel bars which are 14 mm thick. The sculptures are hand bendet, and to me they represent lines in space. They correspond to the lines that you see in my paintings, which I create as part of the artistic process before applying the colours. In this case, I wanted to break free of the flat nature of the canvas by translating them in the third dimension. Surprisingly, the picture communicates with the sculptures, becoming a single object”. From this point of view, we come to the unprecedented realisation that the active artist is not only concerned with forcing the limits of the object- painting or the essence of painting itself, but with the aesthetic and qualitative parameters within which it is observed and/or experienced. Moreover, the Russian doll effect among the “signs” that are on display allows us to observe how the opposing categories of figurative and abstract image, automatic and planned gesture, and history of art and visual memory need to be reconsidered during this era of touchscreens in a digital and globalised world. The artist’s aim with the ‘Trajectory’ project is not so much to exhibit paintings of an abstract nature in comparison with the site-specific concept, but to directly reveal the time needed to “make” the painting and for it to “come to fruition”.

As the curator Lorenzo Bruni writes as part of a conversation that will be presented together with a special edition/poster designed by the artist: “The challenge that Stamkopoulos undergoes is not to apply his particular artistic method of partially removing colour from a surface – which he normally does on canvas – to a location-based work. Rather, it consists of placing the time needed for the artistic process at the centre of the work, and establishing a dialogue between it and the surrounding world, which does not exist independently. It is this requirement that leads to the decision to use the same colour tones for the wall painting as those which characterise the cityscape that exists outside the windows of the gallery, although here they are freed from their function of “defining” forms and objects

This perceptual permeability between interior and exterior, like the one between art and life, together with the context of “Rome” in which all of this takes place, highlights aspects that would not have come into focus so sharply on other occasions: 1) the fact that the composition of monocromatic painterly forms can refer back to fragments of ancient frescoes and the procedures used to preserve them; 2) the act of spray painting used in the tags of urban graffiti artists placed in the context of abstract painting; 3) a response to the aspect of pure decoration that can be associated today with works influenced by Gestalt theory; 4) a study of the idea of the “total work of art” as conceived by Theo van Doesburg, one of the founders of De Stijl, which introduced the concept of the fourth dimension by emphasising the factor of time in creating abstract works; 5) the re-opening of the twentieth century discussion on the balance between background and foreground object; 6) a reflection on what Leon Battista Alberti and the Florentine Renaissance considered a picture: a window that best frames the landscape. […] It is as if the artist had responded to these questions before they even arose, by means of his strategy of exploring the act of painting by transforming it into sculptural blocks, and vice versa”.

The ‘Trajectory’ project was conceived by Stamkopoulos as a shared reflection on his way of working with abstract painting. The intention, however, is to place greater importance on the process rather than the final image. The artist, while assuming the responsibility of reflecting on the legacy of the modernist tradition of monochromaticity and the political/conceptual tradition of analytical painting, aims to make the comparison not by decoding reality on canvas, but by making the viewer aware of their own thought processes, leading them to reflect on the role and communicability of painting today compared to its history stretching back thousands of years

Lorenzo Bruni

Soul Remains at Nathalie Halgand, Vienna

The Greek painter Yorgos Stamkopoulos hasn’t touched a paintbrush in nearly ten years. And indeed, when you behold one of his works, what you see isn’t necessarily a painting at all, but the physical remnants of an invisible act. So Mr. Stamkopoulos, what is the painting? On a recent studio visit, he dropped a tensile plastic tangle at my feet. Here was my answer: pure material.

For Stamkopoulos, painting is not an accumulation of pre-meditated gestures plotted out on a canvas, nor is it an expressive act. Painting is instead something that is removed from the canvas, while his art is that which remains. At first glance, the gaudy skin of plastics seems to posses little relationship to the sleek, minimal canvases that lined the walls of his Berlin studio in preparation for his forthcoming exhibition at Galerie Halgand. However, this enigmatic interplay between process and material forms one of the most compelling aspects of Stamkopoulos’ practice.

For several years now, Stamkopoulos has described his process as “blind painting.” Each of the works in his exhibition Soul Remains begins with a simple, gestural line drawing. This first mark signals both the beginning and the end of the artist’s control over the canvas. Eschewing prescribed outcomes, he alternates airbrushing with applying layers of masking material, which he then peels off to reveal the composition that results from multiple layers of masking and spraying: a kind of camouflage in reverse. This technique of creation through destruction resonates with the work of historical decollage artists like Raymond Hains, Jacques Villeglé, and Mimmo Rotella. Yet while these figures intervened in advertising images to create gritty, lacerated surfaces, Stamkopolous’ adapts this process to more lyrical, ambiguous ends. A phantom liveliness pervades the work in the exhibition. Born of accident and chance these canvases not only contain the trace of the artist’s sole gesture, but also the vestiges of process-based material reactions. While some of the masked areas are blank, others bear a ghostly imprint of lingering materials—almost as if the painting captured itself in the process of disappearing, offering a glimpse of its soul remains.

Jesi Khadivi

Beyond Ancient Space at CAN gallery, Athens

Post-Idolatry

What triggers me quite much when I hear Yorgos talking about his work is the terms he often uses such as psychedelic, transcendental, illusional, et cetera, and the fact that such terms and notions bring me in a sort of an awkward position as they tend to be connected with something supernatural or mystical.

Painting seems to have long departed from any connection to spirituality or theosophy, and any approach towards such notions today seems rather precarious. “Höhere Wesen befahlen: rechte obere Ecke schwarz malen!” (Higher Powers Command: Paint the Upper Right Hand Corner Black!) had Polke written on his 1969 homonymous painting, and in this way even though the ‘Higher Powers’ were questioned the upper right corner became indeed painted black.

Approaches on such notions are often today in a humorous way, and at the same time we may hold a critical and precautious stance towards them we can’t actually –at least not entirely- deny or repudiate them.

But what happens then in the case of Yorgos, is it indeed in search of something mystical or spiritual?

Yorgos works in a highly intuitional way, sometimes under the influence of heavy metal music, and quite often without having direct control of the result of his painting –the latter comes through the processes he follows in his work, in what he calls ‘Blind painting’. Though, as painting in a subconscious way belongs rather to the myth, the endeavor of working in a highly intuitional way goes down to a play between allowing and restraining. What fascinates me in the work of Yorgos is that he manages to enhance it with a feeling of a different dimension. This though occurs not through the heaviness of the quest of something that aspires to be spiritual but rather comes through a more loose way, and the feeling of a different dimension mainly stems from a sense of space that is created within his images. Considering the different series of his work, it may either take the form of a landscape –through the horizontal, spray painted, blended stripes of different colors; or through a form of a fragmented space –through the various masked layers of paint that simultaneously create depth in the image and are also projected towards the beholder. The space in the latter becomes vibrating and this I find an attribute of his more recent ‘painterly’ works, as the more gestural forms become floating in a kind of an absurd landscape-space.

This sense of a fragmented, vibrating space –what gives me the feeling of a different dimension- is a significant part of his work and probably the reason he likes using terms as the ones I mentioned above. It also shows his attitude towards his work but also towards painting in general –a quest to become a passageway to something ‘Higher’ while this is seen in a more light and loose manner.

Giorgos Kontis

New Dawn at CAN gallery, Athens

“Art is not, it does not exist as part of a continuous presence and of a continuous representation. It does not comprise an event that is, which is there, but unfolds in spacetime in a very specific way, in its own world, which it makes available to the world. It gives while at the same time it withdraws, provides and takes back what it offers, it inspires its -destined to collapse- interpretations.” (Kostas Axelos, The Opening towards the Upcoming and the Enigma of Art)

Very much influenced by music the artist composes complex colorful landscapes, which he then baptizes with various song titles. Music at this point though is a little bit more than just a point of inspiration. It sets the identity of his works and gives the work a rythmical tempo that painterly translates into parts full of intensity and strongly symmetrical color fields. Bright, full of bold color contrasts, these ‘spiritual landscapes’ are in conflict with the natural inclination of the human mind towards order and measure. They open a window into a world full of sensations. There is nothing quite about Stamkopoulos’ paintings, like there is nothing predictable or strictly pre-planned about them. If these works were words they would be shouting and if they were a song it would definetely be loud.

Up until now, the artist has been working synthetically, analyzing color and then putting it back together in a manner that it may have seemed chaotic but was actually quite methodical and planned. In his new series of works Stamkopoulos makes a huge turn and embraces chance in order to minimize the influence of his conscious upon painting for a result that is rather random and unexpected. The artist paints his canvases in many successive layers that overlap each other, leaving some uncovered and some blind areas which then in turn he covers with color while he repeats the same gesture over and over again. The final composition is not visible to him at any point in this procedure until the end, when the final layer is applied and complete and the colorblind areas are uncovered.

This way Stamkopoulos manages to isolate each layer from the next in order to concentrate in color and in the rythm of his airbrush. The ability to work on each layer separately offers an unprecedented sense of freedom which translates directly to the viewer as core emotion. This clear and simple creative process becomes the vehicle of this complex painting experience and defines Stamkopoulos’ artistic language which aims to express both emotions and more abstract, metaphysical concepts, which lie outside the realm of consciousness.